The Uninvited Guest

31 Oct

Published in American Book Review. View more.

31 Oct

I wrote “Christianity, Wild Turkey, and Syphilis.” This was published in the Journal of Biblical Interpretation. Search Results for H. Aram Veeser | Brill

24 Oct

I wrote “The Case for Armenians as Indigenous People.” Published in Journal of the Society for Armenian Studies.

24 Oct

I wrote this article which is now published as “Said’s Worldliness,” in a newly released volume called Theory as World Literature, ed. Jeffrey Di Leo (Bloomsbury, 2024).

24 Oct

I was the guest editor of JPW issue 60.4, “Postcolonial Interviews.” I wrote the introduction and also the final article in the issue, as well as commissioning the other articles and organizing the whole issue. My introduction is open access and free to all. If anyone wishes access to any of the other articles, they should write to me at .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address).

15 Feb

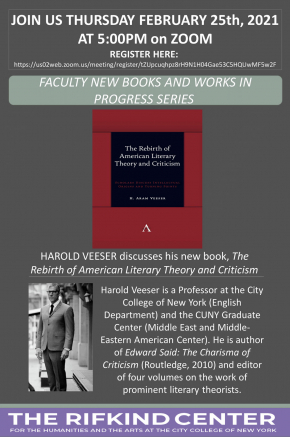

FACULTY NEW BOOKS AND WORKS IN PROGRESS SERIES

HAROLD VEESER discusses his new book, The Rebirth of American Literary Theory and Criticism

THURSDAY FEBRUARY 25, 2021

AT 5:00PM on ZOOM

06 Feb

March 2015

Theme of the meeting: The ‘charisma’ of critics: how do intellectuals make their way in the world, immprovise, perform, and enthrall?

08 Jul

I spoke with Neema Parvini from “Shakespeare and Contemporary Theory”

In this episode: experiences of studying under Edward Said; the birth of the theory journal; how new historicism collapsed traditional divisions between historical scholarship and criticism; the movement for ‘professionalism’ in the US academy in the 1980s; the development of Marxist theory in America; Greenblatt’s concept of salutary anxiety and arbitrary connectedness; the history of ideas vs. human experience and how new historicism differs from the older historicism represented by E.M.W. Tillyard; thoughts on evolutionary criticism; and new historicism and academic distance.

Here’s the MP3, or go the website.

07 Dec

“Veeser, H. Aram. Edward Said: the charisma of criticism. Routledge,

2010. 260p bibl index ISBN 9780415902649, $39.95

Coauthor (with Dana Self and Linda Nochlin) of the essays in the

exhibition catalog Ken Aptekar: Painting between the Lines, 1990-2000

(2001) and editor of The New Historicism (1989) and The New Historicism

Reader (I 994), Veeser (City College of New York) has written a

beautifully crafted examination of the legacy of the renowned

Palestinian literary critic, who died in 2003. Nearly two decades in

the writing, the book is neither hagiography nor attack. In each

chapter, the author provides a discussion (often dense) of Said’s

relationship with an intellectual or political movement, followed (and

mirrored) by a vignette of Veeser’s tortured relationship with that

movement’s particular critic or exponent. Among the topics: nonlinear

thinking, Orientalism, Swiftian satire, and religious criticism. Each

facet of Said’s thought falls within Veeser’s definition of charisma,

the powerful appeal of the individual within an institution. Veeser

suggests that Said’s foray into world politics was disappointing

because of his failure to consider the individual as always socially

embedded and, thus, not fully autonomous. None of this, Veeser argues,

detracts from Said’s charisma in the classroom, where he was most

brilliant and rhetorically effective, as evidenced by his many

successful students. Summing Up: Recommended. ** Upper-division

undergraduates through faculty.—B. A. McGowan, Moraine Valley

Community College”